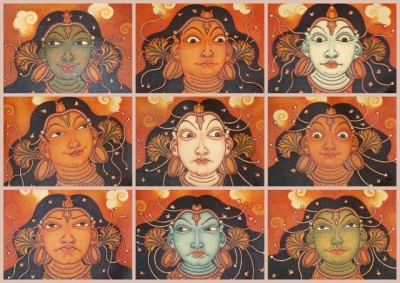

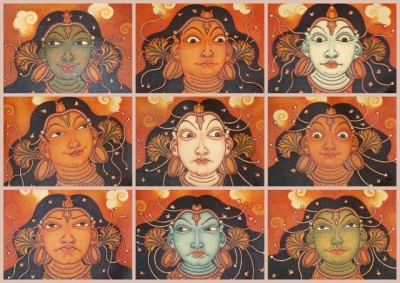

Five years ago, in one of the workshops offered by our teachers at Ritambhara, I underwent a theatre exercise where I had to enact a narration of an imagined story that spans all the navarasas, embodying each of them as best as I could. In that story, bibhatsam (disgust) leads to raudram (rage), which, with sufficient insight into the other's psychological condition, leads to karunyam (compassion).

I was able to evoke the different rasas with varying degrees of ease. Among the easier ones for me was karunyam and the most difficult, raudram. When we had to make a drawing locating the different rasas in our bodies, I couldn’t place raudram anywhere. I shared with Raghu “As soon as I experience rage, I am able to see the suffering of the person I am angry with and end up feeling only compassion!” He casually responded “Check with your mind if it is not making up a convenient story about this in order to distract you. It can be very smart.” and left. Something about what he said shook me. That evening, when I was with my partner, I exploded with rage in one of the most intense ways I'd ever had and was shocked! On the next day at the workshop, I shared that raudram was the only rasa I could feel all over my body.

Until that event, with all the things that my intelligent and smart mind had worked out about 'human suffering' and 'healing', I thought I had 'cracked' compassion fairly well. When I saw an oppressor, I could instantaneously feel compassionate towards him or her “He must have had a difficult childhood! He needs healing!” were words that came most naturally to me. I thought I was a natural at this! I thought I had done a lot of inner work through Buddhist practices and mindfulness and had pretty much transcended anger. But

apparently not! I realised that I had a very underdeveloped ability to

experience and hold a healthy raudram, and had a lot of work to do there.

Until that event, with all the things that my intelligent and smart mind had worked out about 'human suffering' and 'healing', I thought I had 'cracked' compassion fairly well. When I saw an oppressor, I could instantaneously feel compassionate towards him or her “He must have had a difficult childhood! He needs healing!” were words that came most naturally to me. I thought I was a natural at this! I thought I had done a lot of inner work through Buddhist practices and mindfulness and had pretty much transcended anger. But

apparently not! I realised that I had a very underdeveloped ability to

experience and hold a healthy raudram, and had a lot of work to do there.

Now, let’s take a look at my / our larger cultural context and its relationship with raudram. It is somewhat permitted, or at least understandable, when a man expresses it. But a woman anywhere in the world is rewarded only for being “polite, nice, kind, soft-spoken, smiling, helpful, patient, forgiving” and so on, and is invariably judged for expressing rage.

One half of my issue was that I was born a pacifist, averse to emotional drama of any kind, avoiding conflicts at all cost and wanting ‘only peace’. And this half holds a very genuine aspiration for love and peace too. It is a very real longing, with nothing superficial or fake at all about it. I hate to see anyone hurt, and hate it even more to be the cause of that hurt for anyone, especially those dear to me. So, I had always withheld my expression of anger for fear of hurting someone, or losing their friendship.

The other half of my issue was that I internalised the voice of the world about me. “Sangee is a lovely person. She never gets angry.” I internalised as my own. But being a free-spirited and an extremely sensitive being, life had a continuous supply of violations of all kinds: physical, emotional and whatever else. There was enough substance to ensure a continuous flow of rage, which I learnt to swallow wholesale as a way of coping and being that ‘nice person’ in my and others eyes. But my body kept meticulous score of every iota of that swallowed rage.

The workshop was not only the very first time a context had given me the license to touch and experience raudram without any judgment, but also told me “It’s problematic when you do not learn to experience and express it”.

Paying attention to where all my rage could be hiding, led me to discover my deeply-hidden shadow self: the passive-aggressive, emotionally cold, binge-eating, the obsessive-compulsive and controlling part of the visibly polite, nice, kind and compassionate Sangee. This was the part of myself that I had shamefully hidden from the world, and from myself. And this was the part that used to regularly surface (by erupting in the most unexpected and unprepared of times!) in my intimate spaces. My way of compensating for not being able to express raudram would be to withhold love and turn cold, slam the coffee mug on the table as I offered it with a plastic smile on the face. And then feeling shameful. And then doing something to distract myself from my feeling of shame. And on and on went the cycle. A powerful name for this behaviour is ‘the tyranny of the weak’. Ruth King has explored in great detail all the ways swallowed rage can erupt in our lives. 'Healing Rage' has helped me along my journey as well!

For a big part of my life, I have suffered a few undiagnosable ailments both mental and physical. The mental one has been periodic episodes of dysfunctionality and darkness. The physical one used to be periodic episodes of muscle weakness with no clinical diagnosis, often so extreme that I’d be bedridden for days, weeks and sometimes months together. Exhausting allopathic, ayurvedic and a few other therapies, I turned to clairvoyants and psychic healers. Some of them, including Dr. Mona Lisa told me “Your body is carrying a lot of trauma.” Over the years, acknowledging and giving safe space for expressing some repressed parts of myself, I believe, have hugely helped me heal through these ailments. (These stories of healing are interesting in themselves, and are for another time!)

Another expression of this psychological shadow-phenomenon was to get triggered by and strongly judge anyone who expressed raudram as “so uncool, immature, uncivilised, unsophisticated and unevolved!”

As I was coming more and more face-to-face with my own shadow and understood the need to own it and integrate it, other co-travelers helped me in the journey by inviting me to spar with them in safety. Just knowing that it was ok to express anger and fight with someone was a completely new experience for me; an immense relief. Over time, practising raudram has gotten a tad easier. But there is still a long long way to go!

According to Sri Krishnamacharya, whose lineage I learn Yoga from, the yogic definition of a psychologically mature person is one who can experience all the navarasa at ease and at will, deploy them at appropriate times and with mastery over them. Shantam is a state of alignment of all the navarasas, and not the absence of raudram, bhibatsam or any of the “undesirable” rasas. It is a state where they are neither dominating, nor suppressed but are in alignment and balance with all the other rasas, and leave no residues when experienced. It is a transcendental state. In order for a state to be transcendental, it must not reject anything. It must include, integrate and rise above.

According to Sri Krishnamacharya, whose lineage I learn Yoga from, the yogic definition of a psychologically mature person is one who can experience all the navarasa at ease and at will, deploy them at appropriate times and with mastery over them. Shantam is a state of alignment of all the navarasas, and not the absence of raudram, bhibatsam or any of the “undesirable” rasas. It is a state where they are neither dominating, nor suppressed but are in alignment and balance with all the other rasas, and leave no residues when experienced. It is a transcendental state. In order for a state to be transcendental, it must not reject anything. It must include, integrate and rise above.

In J. Krishnamurthy's words:

“This loving-kindness, compassion and love (metta) is not an intellectual exercise.... this quality cannot be cultivated, cannot be practised, cannot be brought about; but it must happen as naturally as breathing, as fully with great joy and delight as the sunset.... You become kinder by observing yourself when you are unkind. Not by trying to be kind.”

Our yoga teachers have a better word for shadows: the disowned parts of ourselves, which then become dysfunctional parts of ourselves. Learning to recognise and accept our disowned and dysfunctional parts is really the only ‘work’ to be done. When we do this as honestly and sincerely as possible, the process of integration happens on its own. This is what I understand Sri Aurobindo calls ‘Integral Yoga’.

Sri Aurobindo's Integral Yoga talks of the need to fully inhabit, include the gifts of and transcend every level of our being. It is also expressed and experienced in a beautifully poetic way in the Nayika’s Quest in ancient Tamil literature, another powerful offering at Ritambhara. It is the evolutionary journey the Consciousness undertakes through the various chakras within our bodies.

In a cultural context, Sri Aurobindo has talked a lot about the underdeveloped kshatriya dharma of the Indian race which has conditioned itself to by-pass the swadhistana chakra, the seat of the vital being. He says the Indian race's weak swadhisthana is also the reason for all the invasions that this land has largely passively received (though there have been pockets of active resistance), endured, suffered and been damaged from. He talks about the need to fully enliven the kshatriya dharma of the race (the warrior's ability to experience raudram), which I see as an extension of my own psychological unlocking. We call it the awakening of the Bhima archetype in our work through the Mahabharatha.

“Avatar: the Last Air Bender” has given me with one of the most powerful imagery to work with over the past two years of my sadhana of integral yoga. I so connect with Aang, his angst for the world, his idealising of ‘forgiveness and compassion’ over everything else, his lack of awareness of or control over intense energies that flow through him often leaving him hurt, his high vata-prakriti and ability to generate new ideas by the minute but without focus or patience, his optimism, his fears, his constant restlessness to act, his ease with water-bending (healing abilities). All these, while he struggles so hard with earth-bending (grounding) and fire-bending (rage).

Aang’s fire is extremely weak. He also has a deeply ingrained memory of once hurting his dearest Katara with his fire which went out of control. Since then, he also a deep fear of fire-bending. "I can't do it. I might end up hurting someone!" is the voice that keeps ringing within and holding him back.

Zuko who used to be a fairly good fire-bender loses his ability as he switches from the asuric to the daivic side of the war. He needs to discover and learn fire-bending himself from a very different source. Aang and Zuko travel all the way to the dragons, who are the original source of fire-bending and learn the art from them through a beautifully synchronous dance. The fire that they can now make and bend is of a very different nature. It is colourful and brilliant like they have never seen before! That’s the only fire that is able to meet and confront even what seemed like the invincible Azula’s lightening. This daivic fire (as I call it) is born from the need to restore dharma, and not out of hatred towards anyone or the need to control.

Even since childhood, the Tamil mystic activist-poet Subramania Bharathi’s call ‘Raudram Pazhagu’ always attracted me, perhaps because it was a secretively-held aspiration. And among all the different masters I have quoted through this article, Bharathi’s call to “practise rage” is the most alive one for me right now. It is interesting to note that Bharathi and Aurobindo were fiery people who were also great friends and co-travellers during their time in Pondicherry. And it is the same Bharathi who also composed and sang “Pagaivanukkarulvaai” (Bless your enemy).

Among all the elements, fire is the hardest and the trickiest to master. For that’s the one element that needs to be used most carefully. If it is used carelessly or without sufficient mastery, it can hurt people. Practise becomes more important with this element than with any other.

With my own practise, I have seen many shades and nuances of raudram unfold over time. Raudram that I must express loudly and clearly because my context needs to hear it. Raudram I can fully touch and experience but postpone its expression, for either the context is too fragile for it, or I don't feel ready to take responsibility for and meaningfully respond to the consequences that it can unleash. Raudram that needs to put on hold to be got in touch with and explored later, for the time needs something else to be urgently attended to. Raudram that can be made into a more playful exploration, or a dance. Raudram that needs to be simply delved deep into through a meditative practice and prayer for transformation. Raudram as a rich field for a harvest of important insights. Raudram as a source of conviction for acting in the world to bring about change. And my practise continues to reveal more shades of it. A critical aspect of the practise is to learn to be easy on myself when my raudram goes out of control leading to unintended consequences, and to pick up the courage to own them up with self-acceptance and self-love, apologise, walk on and continue the practise.

But my most important learning of all is to not revel and indulge in raudram, but to fully experience it so I can learn to transcend it into a space of shantam. From that, and only that integrated space, can the war of our times be fought and won. And dharma restored.

Until that event, with all the things that my intelligent and smart mind had worked out about 'human suffering' and 'healing', I thought I had 'cracked' compassion fairly well. When I saw an oppressor, I could instantaneously feel compassionate towards him or her “He must have had a difficult childhood! He needs healing!” were words that came most naturally to me. I thought I was a natural at this! I thought I had done a lot of inner work through Buddhist practices and mindfulness and had pretty much transcended anger. But

apparently not! I realised that I had a very underdeveloped ability to

experience and hold a healthy raudram, and had a lot of work to do there.

Until that event, with all the things that my intelligent and smart mind had worked out about 'human suffering' and 'healing', I thought I had 'cracked' compassion fairly well. When I saw an oppressor, I could instantaneously feel compassionate towards him or her “He must have had a difficult childhood! He needs healing!” were words that came most naturally to me. I thought I was a natural at this! I thought I had done a lot of inner work through Buddhist practices and mindfulness and had pretty much transcended anger. But

apparently not! I realised that I had a very underdeveloped ability to

experience and hold a healthy raudram, and had a lot of work to do there.

***

Now, let’s take a look at my / our larger cultural context and its relationship with raudram. It is somewhat permitted, or at least understandable, when a man expresses it. But a woman anywhere in the world is rewarded only for being “polite, nice, kind, soft-spoken, smiling, helpful, patient, forgiving” and so on, and is invariably judged for expressing rage.

One half of my issue was that I was born a pacifist, averse to emotional drama of any kind, avoiding conflicts at all cost and wanting ‘only peace’. And this half holds a very genuine aspiration for love and peace too. It is a very real longing, with nothing superficial or fake at all about it. I hate to see anyone hurt, and hate it even more to be the cause of that hurt for anyone, especially those dear to me. So, I had always withheld my expression of anger for fear of hurting someone, or losing their friendship.

The other half of my issue was that I internalised the voice of the world about me. “Sangee is a lovely person. She never gets angry.” I internalised as my own. But being a free-spirited and an extremely sensitive being, life had a continuous supply of violations of all kinds: physical, emotional and whatever else. There was enough substance to ensure a continuous flow of rage, which I learnt to swallow wholesale as a way of coping and being that ‘nice person’ in my and others eyes. But my body kept meticulous score of every iota of that swallowed rage.

***

The workshop was not only the very first time a context had given me the license to touch and experience raudram without any judgment, but also told me “It’s problematic when you do not learn to experience and express it”.

Paying attention to where all my rage could be hiding, led me to discover my deeply-hidden shadow self: the passive-aggressive, emotionally cold, binge-eating, the obsessive-compulsive and controlling part of the visibly polite, nice, kind and compassionate Sangee. This was the part of myself that I had shamefully hidden from the world, and from myself. And this was the part that used to regularly surface (by erupting in the most unexpected and unprepared of times!) in my intimate spaces. My way of compensating for not being able to express raudram would be to withhold love and turn cold, slam the coffee mug on the table as I offered it with a plastic smile on the face. And then feeling shameful. And then doing something to distract myself from my feeling of shame. And on and on went the cycle. A powerful name for this behaviour is ‘the tyranny of the weak’. Ruth King has explored in great detail all the ways swallowed rage can erupt in our lives. 'Healing Rage' has helped me along my journey as well!

For a big part of my life, I have suffered a few undiagnosable ailments both mental and physical. The mental one has been periodic episodes of dysfunctionality and darkness. The physical one used to be periodic episodes of muscle weakness with no clinical diagnosis, often so extreme that I’d be bedridden for days, weeks and sometimes months together. Exhausting allopathic, ayurvedic and a few other therapies, I turned to clairvoyants and psychic healers. Some of them, including Dr. Mona Lisa told me “Your body is carrying a lot of trauma.” Over the years, acknowledging and giving safe space for expressing some repressed parts of myself, I believe, have hugely helped me heal through these ailments. (These stories of healing are interesting in themselves, and are for another time!)

Another expression of this psychological shadow-phenomenon was to get triggered by and strongly judge anyone who expressed raudram as “so uncool, immature, uncivilised, unsophisticated and unevolved!”

***

According to Sri Krishnamacharya, whose lineage I learn Yoga from, the yogic definition of a psychologically mature person is one who can experience all the navarasa at ease and at will, deploy them at appropriate times and with mastery over them. Shantam is a state of alignment of all the navarasas, and not the absence of raudram, bhibatsam or any of the “undesirable” rasas. It is a state where they are neither dominating, nor suppressed but are in alignment and balance with all the other rasas, and leave no residues when experienced. It is a transcendental state. In order for a state to be transcendental, it must not reject anything. It must include, integrate and rise above.

According to Sri Krishnamacharya, whose lineage I learn Yoga from, the yogic definition of a psychologically mature person is one who can experience all the navarasa at ease and at will, deploy them at appropriate times and with mastery over them. Shantam is a state of alignment of all the navarasas, and not the absence of raudram, bhibatsam or any of the “undesirable” rasas. It is a state where they are neither dominating, nor suppressed but are in alignment and balance with all the other rasas, and leave no residues when experienced. It is a transcendental state. In order for a state to be transcendental, it must not reject anything. It must include, integrate and rise above. In J. Krishnamurthy's words:

“This loving-kindness, compassion and love (metta) is not an intellectual exercise.... this quality cannot be cultivated, cannot be practised, cannot be brought about; but it must happen as naturally as breathing, as fully with great joy and delight as the sunset.... You become kinder by observing yourself when you are unkind. Not by trying to be kind.”

Sri Aurobindo's Integral Yoga talks of the need to fully inhabit, include the gifts of and transcend every level of our being. It is also expressed and experienced in a beautifully poetic way in the Nayika’s Quest in ancient Tamil literature, another powerful offering at Ritambhara. It is the evolutionary journey the Consciousness undertakes through the various chakras within our bodies.

In a cultural context, Sri Aurobindo has talked a lot about the underdeveloped kshatriya dharma of the Indian race which has conditioned itself to by-pass the swadhistana chakra, the seat of the vital being. He says the Indian race's weak swadhisthana is also the reason for all the invasions that this land has largely passively received (though there have been pockets of active resistance), endured, suffered and been damaged from. He talks about the need to fully enliven the kshatriya dharma of the race (the warrior's ability to experience raudram), which I see as an extension of my own psychological unlocking. We call it the awakening of the Bhima archetype in our work through the Mahabharatha.

***

Aang’s fire is extremely weak. He also has a deeply ingrained memory of once hurting his dearest Katara with his fire which went out of control. Since then, he also a deep fear of fire-bending. "I can't do it. I might end up hurting someone!" is the voice that keeps ringing within and holding him back.

***

Even since childhood, the Tamil mystic activist-poet Subramania Bharathi’s call ‘Raudram Pazhagu’ always attracted me, perhaps because it was a secretively-held aspiration. And among all the different masters I have quoted through this article, Bharathi’s call to “practise rage” is the most alive one for me right now. It is interesting to note that Bharathi and Aurobindo were fiery people who were also great friends and co-travellers during their time in Pondicherry. And it is the same Bharathi who also composed and sang “Pagaivanukkarulvaai” (Bless your enemy).

Among all the elements, fire is the hardest and the trickiest to master. For that’s the one element that needs to be used most carefully. If it is used carelessly or without sufficient mastery, it can hurt people. Practise becomes more important with this element than with any other.

With my own practise, I have seen many shades and nuances of raudram unfold over time. Raudram that I must express loudly and clearly because my context needs to hear it. Raudram I can fully touch and experience but postpone its expression, for either the context is too fragile for it, or I don't feel ready to take responsibility for and meaningfully respond to the consequences that it can unleash. Raudram that needs to put on hold to be got in touch with and explored later, for the time needs something else to be urgently attended to. Raudram that can be made into a more playful exploration, or a dance. Raudram that needs to be simply delved deep into through a meditative practice and prayer for transformation. Raudram as a rich field for a harvest of important insights. Raudram as a source of conviction for acting in the world to bring about change. And my practise continues to reveal more shades of it. A critical aspect of the practise is to learn to be easy on myself when my raudram goes out of control leading to unintended consequences, and to pick up the courage to own them up with self-acceptance and self-love, apologise, walk on and continue the practise.

But my most important learning of all is to not revel and indulge in raudram, but to fully experience it so I can learn to transcend it into a space of shantam. From that, and only that integrated space, can the war of our times be fought and won. And dharma restored.

2 comments:

As someone who's exploring the jathara agni, I very deeply resonate with this! Much love Sangi..

Beautiful! Thank you sharing this.

Post a Comment